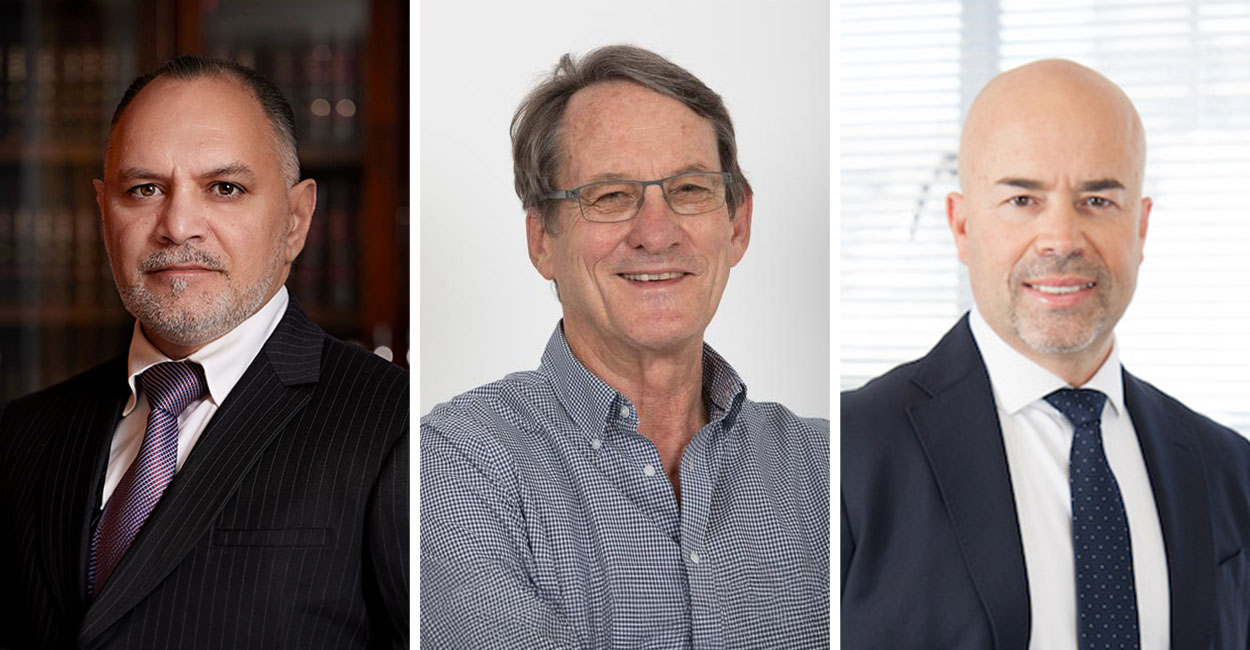

MAIN IMAGE: Chantelle Gladwin-Wood, partner and Anja van Wijk, senior associate at Schindlers Attorneys.

The finalising of the Expropriation Bill is one of the priority tasks set before the sixth Parliament.

The much-debated Bill is expected to be tabled soon by the Department of Public Works and Infrastructure. Government has been pushing for it to be finalised – just last week Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation Minister Lindiwe Sisulu told Parliament her department should have first innings on expropriated land near urban settlements to use for affordable housing since that is in the public interest.

The reworked Bill that was published last December noted five ‘types’ of land that maybe expropriated without compensation – if it’s in the public interest. The list includes land that is used or occupied by a labour tenant, land acquired purely for speculation, state-owned land, abandoned land and land where the market value is less than or equal to the amount already invested by the state.

Where does that leave private property owners? What about landowners that have a mortgage? Chantelle Gladwin-Wood, partner and Anja van Wijk, senior associate at Schindlers Attorneys earlier this year looked at some of the fundamental legal issues surrounding expropriation without compensation (“EWC”). The following is an extract from their article ‘The Expropriation Bill of 21 December 2018’:

The Bill creates and protects different types of right holders differently. Broadly speaking there are three classes: owners, registered right holders and unregistered right holders. The general idea is that all persons with any type of rights in the property being expropriated should be compensated (unless it is just and equitable not to compensate them) but they are all given the opportunity to make submissions in relation to the value of their rights.

Owners

All owners are entitled to compensation (unless it is just and equitable not to pay them any compensation).

Registered right holders

The Bill provides that (unless the expropriating authority expressly expropriates the registered right at the same time as expropriating the ownership of the property concerned) registered real rights remain intact and unaffected by the expropriation.

Mortgage bonds

There is one exception to the rule stated above pertaining to registered real rights, and that is in relation to mortgage bonds. Bonds are not protected as registered real rights and section 9(d) prescribes that the effect of expropriation is that the ownership of the property passes to the expropriating authority free of any unregistered rights, but with all registered rights (apart from bonds) remaining intact. This is interesting because the Bill does not state that the bond is being expropriated – in fact, it goes to pains to avoid saying this. This might be an attempt to avoid a judgment that the bonds are being expropriated too (because they are not ‘taken’ in the way that the property is ‘taken – they just cease to bind the new owner, who is the state – and they remain enforceable against the old owner who was expropriated). So, although the bond holder loses its security for the repayment of the loan, it does not lose the right to claim that repayment. Although the bond holder is entitled to receive notice of the intention of the expropriating authority to expropriate, it is not entitled to receive the expropriation notice itself.

The same applies to other registered right holders (presumably because the other registered rights remain intact and are not affected by the expropriation unless they too, in addition to the ownership, are expropriated, in which case they must be dealt with as if they were ownership and compensated according to the same principles). The bond holder is entitled to make representations as to why/how its rights are affected and as to the value of its right but is not entitled to compensation therefore. We anticipate an interesting court challenge by the banks and by persons expropriated with bonds on the basis of the allegation that the security right (as opposed to the claim for payment) might in some cases be of separate value in terms of section 25 of the Constitution. This was recognised as a possibility by the Constitutional Court in the case of Jordaan and Others v City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality and Others [1].

Unregistered rights

Understandably it is more difficult to protect unregistered right holders because it is not apparent that there are any unregistered rights without (sometimes extensive) investigation. There might be cases where this is fairly obvious (for example where tenants are concerned) but it might be very difficult otherwise to detect the existence of and track down the holders of unregistered rights in the property in question. The Bill makes a special effort to protect unregistered right holders who are not initially detected and advised of the expropriation. A special level of protection is given to builder’s liens, the rights of a purchaser of the property, and unregistered leases inasmuch as the owner of the property is obliged to notify the expropriating authority of the existence of such unregistered rights when the expropriating authority sends the owner the first notice of intention to expropriate, and thereafter the expropriating authority must deal with those unregistered rights and (if just and equitable) compensate the holders thereof separately to the ownership.

Rights to enforce payment

The Bill contemplates that (notwithstanding whether payment has been made or not) the state can take possession on the date referred to in the expropriation notice. The Bill provides little recourse for a person who has not been paid their compensation at the time or at all. They are essentially forced (after giving notice to the expropriation authority to demand payment) to approach a court for assistance. The state is reputed to be a bad payer in several kinds of cases (such as RAF claims, certain welfare grants, and for some tender contracts) and it is expensive and time consuming for a person affected by non-payment to have to approach a court. Ideally a more friendly mechanism of encouraging/enforcing payment could be introduced, one that motivates the state to pay without operating unduly harshly against it, such as mediation, or perhaps not allowing the state to take possession of the expropriated property until such time as payment has been made in full.

Atypical ‘registered’ rights

The definition of ‘registered’ (in relation to rights) includes registration in any government office in terms of any law. It is not limited to registered rights in land. An interesting question arises as to how rights registered in offices other than the Deeds Office will be dealt with – such as where the interests of a bank are noted against the ownership of a vehicle because the bank financed the acquisition thereof. This will qualify as a registered right, but because this is not a mortgage bond the bank will be entitled to compensation if the right is expropriated along with ownership. This will (presumably) have to happen if the expropriating authority wants to expropriate the vehicle because the bank’s interest is registered against the title of the vehicle and (presumably) the bank’s interest in the vehicle cannot remain intact after the expropriation because the vehicle vests in a new owner – i.e. the expropriating authority – unless of course the expropriating authority is taking over the loan. To the extent that the bank is entitled to compensation for the loss of its security (because presumably the bank’s right to claim repayment of the loan as against the person being expropriated will survive the expropriation) it could be argued that a mortgage bond holder should be in the same position and that it is arbitrary not to equate the two types of finance simply because one relates to a movable and the other to an immovable. How the affected parties (and the court) will deal with this will remain to be seen.

End of extract.

Conclusion

President Cyril Ramaphosa has repeatedly gone to great pains to put investors at ease that their property investments will be safe and that there will not be a repeat of the land grabs as happened in Zimbabwe. However, experts have been saying that the president can’t have his bread buttered on both sides – he can’t promise private landowners security and deliver on the promises made that land will be expropriated. Expropriation without compensation is going to happen – what remains to be seen is what this will mean in practice.

References

[1] Jordaan and Others v City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality and Others, City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality v New Ventures Consulting and Services (Pty) Limited and Others; Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality v Livanos and Others (CCT283/16, CCT293/16, CCT294/16, CCT283/16) [2017] ZACC 31; 2017 (6) SA 287 (CC); 2017 (11) BCLR 1370 (CC) (29 August 2017).

Note: *The article was originally published on 28 January 2019 on the website of Schindlers Attorneys and is republished here with the permission of the authors.