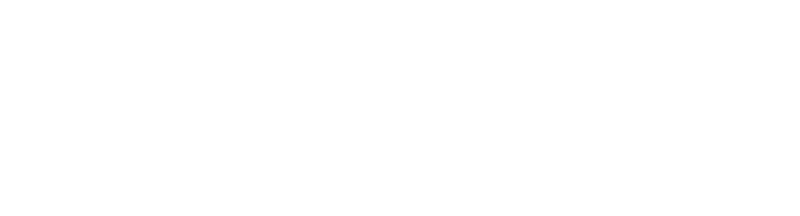

MAIN IMAGE: Robert Krautkramer, director of Miltons Matsemela.

Did you know that under the new Property Practitioners Act, one of the many changes will be that a consumer may claim their money back from property practitioners, even if they are trading without a valid FFC? Robert Krautkramer, director with legal firm Miltons Matsemela, expands on what the new Act says about who will need FFC’s to practice and the consequences of not having a valid certificate.

The Property Practitioners Act (PPA) was recently signed into law. This new piece of legislation will replace the Estate Agency Affairs Act of 1976, but it hasn’t commenced yet. The date for that is yet to be decided, but it is unlikely that it will happen this year, with luck it could take effect towards the middle of 2020.

There is still a lot that needs to be done. New regulations must be drawn up and published. The Estate Agency Affairs Board needs to gear up. The Minister has to first make rules on what training requirements all the property practitioners who will now be joining the fray, need to undergo and the Minister must also publish a code of conduct. So much work still lies ahead before the Act can commence.

Herewith an overview of some of the most significant changes regarding FFC’s.

Current legislation requires estate agents and real estate agencies to annually renew their Fidelity Fund Certificates (FFC), and these are then only valid until 31 December every year. This scenario changes dramatically under the new legislation. Under the new Act a FFC will be valid for three years. As with the present legislation, a valid FFC will be a mandatory requirement for every property practitioner (PP) – not only estate agents. Without an FFC, a PP may not trade or be paid for any work done.

Who will qualify as a property practitioner?

The new Act defines a property practitioner as any person (natural or legal) who in the ordinary course of business, for gain (i.e. against payment), holds out (i.e. this is his/her business), on behalf of another person:

- auctions; rents; sells or exhibits for sale or purchase, property or a business;

- manages property;

- negotiates such an agreement;

- canvasses for landlords/tenants/buyers or sellers of properties/businesses; or

- collects or receives rental on behalf of another person;

- acts as intermediary or facilitator in any of the above (neither are defined in the act but a google definition provides the following):

- intermediary – a person who acts as a link between people in order to try and bring about an agreement;

- facilitator: any activity that makes a social process easy or easier.

- It also includes a home-owners association which does any of the above, for gain; and

- anyone employed by a property practitioner to do any of these things on his / her behalf; and

- includes anyone who sells, or markets time share or fractional ownership (basically a fancy expression for time share) or any interest in property or a development; (In this regard uncertainty exists as to whether the intention is to actually include developers and time share companies themselves – and not only their selling agents. (One interpretation of this sub section could mean that any seller of an interest in any property would be a property practitioner. Then all sellers of land would be seen as property practitioners, which could never have been the intention. Krautkramer is of the view that the definition is probably intended to only refer to those who sell these interests as “agents” on behalf of a developer or time share company); and includes

- anyone who is employed to manage / supervise the day-to-day business operations of a property practitioner (office manager); and also

- anyone who arranges:

- financing for a sale or lease;

- bridging finance (i.e. where a seller wants to take an advance against the proceeds of his sale) or; acts as a bond broker

- except if either of these, fall within the definition of a “financial institution” under the Financial Services Board Act.

- It includes directors of companies; members of CC’s and trustees of trusts, if the entity does any of the above; and also,

- any attorney or person employed by an attorney who renders these services except if that person must hold an FFC with the Attorneys’ Fidelity Fund, and if this work forms part of the attorney’s normal practice.

- If the firm is a company then all of its directors must also have one; if it is a CC, then all its members; if a partnership, its partners; and if a Trust, all the trustees.

Take note: Anyone may apply to the Minister for exemption (partially or entirely from the Act) for up to 3 years at a time.

What is the point of an FFC?

The point of an FFC is to provide the consumer with protection against theft of money that has been entrusted to a PP, such as money meant to buy a house; rental income or rental deposits.

In terms of the new Act, once an FFC is issued to a PP and should that PP then steal money which the PP held in trust, then the consumer can claim this money back from the fidelity fund. All the consumer needs to do is lay a criminal charge and be sure that the PP had an FFC at the time of the theft.

This is a huge change to the current legislation because under the current Estate Agent Affairs Act, the consumer must first try to recover the funds from the PP him/herself, and can then only, claim from the fund. The consumer must first exhaust all available remedies (i.e. sue the PP; get a sheriff to try and attach and sell assets and even possibly sequestrate the PP) before one can claim money from the fund.

As such, this new process will make it much easier for the consumer to claim back stolen money. But a consumer can only claim from the fund if the PP had an FFC at the time of theft!

As such seller; buyer; landlord or tenant, must always insist on seeing the PP’s FFC, which must be valid at the time of the transaction, before paying over one red cent.

Consequences of not having an FFC

If an entity has just one PP in its employ who does not have an FFC, then the entity may not trade. Which means no other PP in its employ may work legally then either.

If a PP was involved in a transaction and did not have a valid FFC at the time of the transaction, then he/she may not claim commission. If the consumer finds out that the PP did not have an FFC at the time of the transaction, then the consumer has 3 years within which to claim it back and if the PP does not pay it back immediately, he/she will be guilty of a criminal offence.

This is also a massive change from the current legal position. Currently, agents are also not entitled to be paid if they don’t have an FFC – but, if an agent does get paid, the seller cannot claim it back. That will become a thing of the past.

The Act also states that if a PP does receive payment when he/she did not have an FFC, then the PP is required to pay the commission to the Fidelity Fund.

However, (and this may be impossible to believe), but this is what the Act states, if the consumer then claims it back from the Fund, the Fund may pay whatever amount (if any) to the consumer which is “equitable in the circumstances”.

Once again, a reminder to all consumers – they must make sure their PP has a valid FFC.

This is the first article by Robert Krautkramer in a new series on the Property Practitioners Act. Next week he will look at the new position of conveyancing attorneys and speak more about the practical aspects around FFC’s.

About the author: Robert Krautkramer has been a partner at Miltons Matsemela Inc since 2011, a boutique law firm that focusses almost exclusively on property law. He has 23 years’ experience all in all as an admitted attorney and regularly presents seminars to estate agents on contract law; the Estate Agent’s Code of Conduct and new relevant legislation, such as the PPA; the Expropriation Bill; and FICA. In 2019 alone he says he addressed around 2000 estate agents on these three topics.